Mostra di arte sacra

Fons Vitae

Di Peter Brandes, Maja Engelhardt, Susan Kanaga e Filippo Rossi

24 Aprile – 6 Giugno

Introduzione di Timothy Verdon

Il titolo della loro installazione, Fons Vitae – Fonte di Vita – echeggia San Paolo, che per primo collegò le acque del Battesimo con la Pasqua, insegnando che i “battezzati in Cristo Gesù” – quelli che scendono nel fonte cioè – sono “sepolti insieme a lui…affinché, come Cristo fu risuscitato dai morti…così anche noi possiamo camminare in una vita nuova” (Lettera ai Romani 6, 3-4).

Il Sepolcro dell’Alberti rimanda infatti al Battistero fiorentino, citandone le tarsie marmoree bianco-verdi, e questa allusione definisce l’impianto della mostra. La base del Sepolcro quattrocentesco tracciata sul pavimento viene trasformata in luce da Peter Brandes, mentre a destra e sinistra sculture di Maja Lisa Engelhardt ne evocano il miracolo. Sopra le scale, poi, tra i fiori dipinti da Susan Kanaga, Filippo Rossi raffigura il mondo nuovo evocato nell’Apocalisse, in mezzo al quale scorre “un fiume d’acqua viva, limpida come cristallo” e cresce “un albero di vita”. Le pietre realizzate dalla Kanaga lungo il fiume, aprendosi ed emanando luce, ricordano che quell’albero “dà frutti dodici volte all’anno, portando frutto ogni mese” e che le sue foglie “servono a guarire le nazioni” (Apocalisse 22, 1-2).

Un sogno pasquale

L’impressione complessiva, nel buio della cripta di San Pancrazio, è di un sogno nato dalla Pasqua: un sogno di luce, di bellezza, di vita. Visto dall’area corrispondente al transetto della sovrastante chiesa, questo sogno contemporaneo ripropone la visionarietà immaginata dall’Alberti, il cui Sepolcro occupava uno spazio del tutto diverso da quello della navata di San Pancrazio, da cui era originalmente visto. Nel sogno contemporaneo, poi, come in quello quattrocentesco, tale alterità comunica speranza, che Alberti esprimeva coll’architettura classica rediviva, e Brandes, Engelhardt, Kanaga e Rossi con la luce e il movimento di un cosmo rinnovato.

In ambo i casi – oggi come nel Quattrocento – il sogno è narrato con simboli. Ma là dove Alberti, chierico, usava la storia, evocando ‘rinascenza’ col ripristino del passato, i laici Brandes, Engelhardt, Kanaga e Rossi recuperano la Bibbia, parlando di ‘risurrezione’ mediante luce, acqua, e la natura rifiorita. Nello spirito dei Profeti e dei Salmi cercano i simboli nel cosmo, facendosi interpreti del moderno umanesimo ecologico, più universale dell’umanesimo archeologico del Rinascimento, che pure includeva la componente ‘natura’. Nella Risurrezione di Cristo di Piero della Francesca, ad esempio – praticamente coevo al Sepolcro albertiano -, oltre al corpo statuario del Risorto e al sarcofago classico, sullo sfondo vediamo alberi disposti con evidente intenzione simbolica: a sinistra, dove comincia la lettura dell’immagine, sono nudi e invernali; poi, a destra, dove lo sguardo arriva passando per la figura del Risorto, sono folti e primaverili. O ancora, nel Battesimo di Cristo di Piero, accanto al corpo statuario del Salvatore cresce un albero a ricordo della similitudine biblica dell’uomo beato che, evitando il male, “è come albero pianto lungo corsi d’acqua, che dà frutto a suo tempo: le sue foglie non appassiscono e tutto quello che fa riesce bene” (Salmo 1, 1-3).

L’uomo e il cosmo–simboli che si completano

La posizione centrale che nei dipinti quattrocenteschi fu assegnata al Cristo viene data ora – nell’installazione di Brandes, Engelhardt, Kanaga e Rossi – allo spettatore, che si trova, lui o lei, a salire in persona dal Sepolcro verso un cosmo redento e l’albero di vita. Lo spettatore non solo contempla i simboli cosmici, cioè, ma in essi dimora, scoprendosi protagonista nel dramma neotestamentario in cui l’uomo è chiamato a liberare la Natura. “L’ardente aspettativa della creazione, infatti è protesa verso la rivelazione dei figli di Dio”, afferma Paolo, spiegando che “la creazione infatti è stata sottoposta alla caducità…nella speranza che anche la stessa creazione sarà liberata dalla schiavitù della corruzione per entrare nella libertà della gloria dei figli di Dio” (Romani 8, 19-21). In questo processo, il rapporto tra la creazione e l’essere umano è intimamente fraterno, perché se da una parte “tutta insieme la creazione geme e soffre le doglie del parto fino a oggi”, dall’altra “anche noi che possediamo le primizie dello Spirito, gemiamo interiormente aspettando l’adozione a figli, la redenzione del nostro corpo” in cui verrà liberata anche alla Natura (Romani 8, 22-23).

Brandes, Engelhardt, Kanaga e Rossi ci restituiscono quindi il nostro ruolo nel sistema simbolico che la Bibbia legge nel cosmo. Ora, secondo il Dizionario Treccani, il termine ‘simbolo’ (σύμβολον) nel greco antico significava “segno di riconoscimento” o di “accostamento”, e deriva da συμβάλλω, “mettere insieme, far coincidere» (composizione di σύν «insieme» e βάλλω «gettare»). Nell’uso degli antichi, era un mezzo di riconoscimento costituito da ognuna delle distinte parti ottenute spezzando irregolarmente in due un oggetto, che i discendenti di famiglie diverse conservavano come segno di reciproca amicizia. Nelle religioni misteriche, poi, ‘Simbolo’ era anche la formula che serviva di riconoscimento tra gli iniziati, e nel cristianesimo divenne il compendio delle fondamentali verità che il candidato al battesimo doveva recitare come segno e manifestazione della propria fede.

L’installazione dei quattro artisti fa tutto questo. ‘Accosta’ il Sepolcro trasfigurato all’acqua del fiume e alla vitalità del giardino in cui cresce l’albero, invitando a ‘riconoscere’ nella tomba vuota di Pasqua il segno dell’amicizia di Dio per l’umanità. Dal Sepolcro di Brandes all’albero di Rossi, la morte si trasmuta in sorgente di vita, e i pochi passi in riva al fiume che lega i due simboli misurano il passaggio dal mistero creduto al miracolo vissuto: il pellegrinaggio che tutti siamo chiamati a fare, come in antiquo s’andava a Gerusalemme, al Sepolcro, per poi tornarvi rinforzati.

Simbologia e sentimenti

Secondo un teologo africano del IV-V secolo, Agostino d’Ippona, questo tipo di comunicazione, che obbliga ad ‘accostare’ e mettere in relazione i diversi frammenti di un’unica realtà, ha straordinaria forza emotiva. Sant’Agostino spiega che, la presentazione della verità mediante segni ha il potere di accendere ed accrescere quell’ardente amore per il quale noi, come fiamme che obbediscono alle leggi della natura, gravitiamo verso l’alto e contemporaneamente verso le profondità, cercando un luogo di riposo. Presentate in questo modo, le cose ci commuovono ed attivano le nostre emozioni molto di più che se venissero esposte con la mera ragione […]. Credo che le emozioni vengano meno facilmente accese mentre l’anima è assorta nelle cose materiali; ma quando essa viene condotta a segni materiali di realtà spirituali, e da questi poi verso le cose che i segni rappresentano, allora l’anima si rafforza nell’atto stesso di passare dagli uni alle altre, appunto come la fiamma di una fiaccola che, muovendosi, arde sempre più intensamente.[1]

Per Alberti, in una cultura satura di conoscenze bibliche, i segni capaci di “accendere ed accrescere” l’amore per Dio erano storici: lesene scanalati, capitelli corinzi e trabeazioni romane che, abbinate alle tarsie del Battistero suggerivano la ‘antichità’ del piano salvifico confermato dalla Pasqua. Per Brandes, Engelhardt, Kanaga e Rossi invece, donne e uomini del presente, i segni sono nell’annuale rinascita della Natura che invita a passare dal fatto materiale a quello spirituale, facendo riscoprire la Bibbia: non quindi l’antichità umana ma l’eternità del Creatore.

Nella cripta dell’antica chiesa monastica di San Pancrazio, l’installazione Fons Vitae ha questo scopo: di trasferirci, almeno per la durata della visita, nella logica eterna dell’amore di Dio.

Timothy Verdon introduction

The title of their installation, Fons Vitae – Font of Life – echoes Saint Paul, who was the first to relate the waters of Baptism to Easter, teaching that those who are “baptized in Christ Jesus” – those who descend into the font, that is -, “went into the tomb with him…, so that as Christ was raised from the dead… we too might live a new life” (Letter to the Romans 6, 3-4).

Alberti’s Sepulchre in fact recalls the Florence Baptistery, reusing its green and white marble inlay, and this allusion defines the present exhibit. The base of the 15th-century Sepulchre, traced on the pavement by Peter Brandes, is transformed into light, and sculptures by Maja Lisa Engelhardt at either side evoke the miracle of resurrection. Above the stairs, then, amid flowers painted by Susan Kanaga, Filippo Rossi depicts the new world described in the Book of Revelation, at whose center is a “river of life… flowing crystal clear” and “trees of life” (Revelation 22, 1-2). The stones placed along the river by Susan Kanaga, open and emanating light, remind us that “the trees bear twelve crops of fruit in a year” and their leaves “are the cure for the pagans”.

An Easter Dream

In the dark crypt of San Pancrazio, the overall impression is that of a dream born at Easter: a dream of light, beauty and life. Seen from the area corresponding to the transept of the overlying church, this contemporary dream replicates the visionary experience imagined by Alberti, whose Sepulchre occupied a space completely different from the nave of San Pancrazio, from which it was originally seen. In the contemporary dream as in the 15th-century one, moreover, such alterity communicates hope, which Alberti expressed through the rebirth of classical architecture, and Brandes, Engelhardt, Kanaga and Rossi with the light and movement of a renewed cosmos.

In both cases – today as in the Quattrocento – the dream is narrated through symbols. Where the cleric Alberti used history, however, evoking ‘renascence’ by restoring the past, the lay artists Brandes, Engelhardt, Kanaga and Rossi rediscover the Bible, speaking of ‘resurrection’ through light, water, and nature in flower. In the spirit of the Prophets and Book of Psalms, they seek cosmic symbols to interpret today’s ecological humanism, more universal than the archeological humanism of the Renaissance, even if this too had a ‘nature’ component. In Piero della Francesca’s Resurrection of Christ, for example – practically contemporary with Alberti’s Sepulchre -, behind the statue-like Risen Savior and classical sarcophagus, the trees in the background have obvious symbolic meaning: at our left, where we begin to read the image, they are winter-bare, while at the right, where our gaze stops after seeing Christ rise, they are in springtime leaf. Or again, in Piero’s Baptism of Christ, next to the risen Christ’s sculptural body a tree recalls the biblical simile of the ‘happy man’ who, because he avoids evil, “is like a tree…planted by water streams, yielding its fruit in season, its leaves never fading; success attends all he does” (Psalm 1, 1-3).

Man and the Cosmos, Complementary Symbols

The central position that Quattrocento artists gave to Christ is now – in the installation by Brandes, Engelhardt, Kanaga and Rossi – assigned to the viewer, who personally ascends from the Sepulchre toward the redeemed cosmos and the tree of life. The viewer not only contemplates cosmic symbols, he or she inhabits them, playing a leading role in the New Testament drama in which human beings set nature free. “The whole creation is eagerly waiting for God to reveal his sons”, Saint Paul says, explaining that although “it was made unable to attain its purpose…, creation still retains the hope of being freed, like us, from its slavery to decadence, to enjoy the same freedom and glory as the children of God” (Romans 8, 19-21). In this process, the relationship between creation and human beings is intimately fraternal, for, on the one hand, “from the beginning to now the entire creation…has been groaning in one great act of giving birth”, and, on the other, “all of us who possess the first fruits of the Spirit, we too groan inwardly as we wait for our bodies to be set free” and to free creation as well (Romans 8, 22-23).

Brandes, Engelhardt, Kanaga and Rossi thus give us back a role in the symbol-system that the Bible sees in nature. According to the Treccani Dictionary, the term ‘symbol’ (σύμβολον) in ancient Greek meant ‘a sign of recognition’ or of ‘matching’, and derives from συμβάλλω, “to put together, make coincide with» (composed of σύν «together» and βάλλω «toss»). In ancient practice, the ‘symbol’ was a means of recognition constituted by each of the separate parts obtained by irregularly breaking an object in two, which the descendants of different families preserved as a sign of reciprocal friendship. In the mystery religions, ‘Symbol’ was also the formula that initiates recited to recognize each other, and in Christianity became the compendium of basic truths that candidates for baptism had to recite as a sign and manifestation of their faith.

Our four artists’ installation does precisely this. It ‘puts together’ the transfigured Sepulchre with the water of the river and the vitality of the garden and tree, inviting us to ‘recognize’ in the empty Easter tomb the sign of God’s friendship for humankind. From Peter Brandes’ Sepulchre to Filippo Rossi’s tree, death becomes a wellspring of life, and our few steps along the river connecting these symbols mark the passage from ‘mystery of faith’ to ‘lived miracle’: a pilgrimage all are called to make, just as people once went to Jerusalem, to Christ’s Sepulchre, returning with new strength.

Simbolism and Sentiment

According to an African theologian of the 4th-5th century, Augustine of Hippo, this kind of communication, which makes us ‘match’ and ‘piece together’ different fragments of a single reality, has extraordinary emotional force. Augustine explains that, the presentation of the truth through signs has the power to ignite and increase that ardent love through which we, like flames obedient to nature’s laws, gravitate upwards and at the same time toward the depths, seeking a place of rest. Presented in this way, things move us and activate our feelings much more than if they were expounded by reason alone…I believe that our feelings are less easily kindled when the soul is absorbed in material things; but when it is led to material signs of spiritual realities, and from these to the things the signs represent, then the soul takes strength from the very act of passing from one to the other, just like the flame of a torch that, as it moves, burns ever more intensely (Epistle 55, 11,21) .

For Alberti, in a culture saturated with Biblical knowledge, the signs able to “ignite and increase” the love of God were historical: fluted pilasters, Corinthian capitals, Roman cornices that, combined with the Baptistery inlay suggested the ‘antiquity’ of a salvific plan confirmed at Easter. For Brandes, Engelhardt, Kanaga and Rossi on the other hand, women and men of the present, the great sign is the annual rebirth of Nature, which calls us to move from material facts to spiritual ones, rediscovering in the Bible not human antiquity but God’s eternity.

In the crypt of the medieval monastic church of San Pancrazio, the installation Fons Vitae has this aim: to situate us, at least for the duration of our visit, in the eternal logic of God’s love.

Peter Brandes

Bio

Peter Brandes (1944) is one of the most significant Danish visual artists alive today. Not only is his oeuvre gigantic, spanning a period of more than fifty years, but his works also enjoy an extraordinary degree of visibility. Brandes is represented in the collections of the most important Danish museums, as well as in those of leading international museums, such as the Louvre. His monumental sculptures and jars are found throughout Denmark, and he has decorated numerous churches in Denmark, Norway, and the United States. In Jerusalem, his powerful Isaac Vase stands at the Holocaust museum Yad Vashem. With regard to technique, Brandes has made use of a wide variety of artistic media: painting, sculpture, drawing, graphics, ceramics, photography, and—last but not least—stained glass, a technique Brandes has breathed new life into.

Nella complessa opera di Peter Brandes per la mostra Fons vitae il dialogo si instaura a più livelli. In primo luogo con Leon Battista Alberti e il suo Sacello del Santo Sepolcro. Brandes ne riprende le proporzioni, non facendone però una copia in scala, bensì rendendo le misure della sua composizione ancora più aderenti alla teoria della concinnitas nel De re aedificatoria (IX, 5-6). La vetrata centrale sul pavimento e quella verticale sono costruite sui rapporti 2/1 e 3/2, le dieci vetrate laterali sui rapporti 1/1 e 3/2, l’intera composizione sul pavimento sul rapporto 3/2 e 6/5. Con l’eccezione dei 6/5 (corrispondente a rapporto musicale di terza minore), abbiamo la traduzione spaziale di rapporti musicali armonici di unisono, ottava e quinta. Maggiore fedeltà alla tradizione pitagorico-platonico-albertiana è difficile immaginare.

Tuttavia questa continuità diventa radicale discontinuità nell’espressione anti-classica dei disegni delle vetrate laterali. Da sinistra a destra, in senso antiorario, Brandes raffigura: la trasfigurazione sul Monte Tabor, la cena di Emmaus, la nascita di Cristo, il mattino di Pasqua, il battesimo di Cristo, il Cristo sulla croce con la spugna di aceto, la deposizione, Maria con Cristo, la resurrezione di Lazzaro, e ancora la trasfigurazione. Senza potermi soffermare su ciascuna figura, il motivo che le accomuna è sempre il passaggio, dalla vita alla morte e dalla morte alla rinascita.

Sulla vetrata verticale Brandes disegna la figura che dal 1980 ha usato quasi come un ideogramma o una firma nella sua scrittura pittorica. Questa forma, in cui Brandes cela, tra l’altro, il profilo dei leoni monumentali a Delo (VI sec. a.C.) e del Mont Sainte Victoire di Cézanne, è stata nei decenni usata da Brandes come una fonte generatrice di sempre nuove forme e motivi.[2]

Al centro della composizione c’è una vetrata gialla che sembra rimandare alle finestre di alabastro del Mausoleo di Galla Placidia a Ravenna: la resurrezione. È la luce della resurrezione che connette tutti gli elementi della composizione. La resurrezione è quella figura senza forma che dà senso alle forme delle dieci figure che la circondano. Così come nel sepolcro vuoto la presenza del risorto sta nella sua assenza fisica.

Disegnando sulla vetrata verticale quello che può quasi essere inteso come un autoritratto, Brandes ha ritratto in esso ciascuno di noi e la capacità che ciascuno di noi ha di generare forme e azioni. La vetrata verticale è puntellata da una scala che sorge dalla vetrata gialla. La luce della resurrezione diventa così il mezzo attraverso cui entrare in dialogo con le storie evangeliche delle vetrate periferiche, ma, infine, diventa anche l’apertura di luce attraverso cui entrare in relazione con sé stessi.

For Peter Brandes art is an uninterrupted dialogue: with Homer, Plato, the Bible, Christian tradition in all its confessional forms, with Judaism, with ancient Egypt, with Nordic sagas, with Friedrich Hölderlin, Søren Kierkegaard, Franz Kafka, Gunnar Ekelöf, Paul Celan. The list, which could be much longer, might seem to favor the pastiches of a postmodern artist. But nothing could be farther from the approach of Peter Brandes, who is guided by the European ideal of humanitas rooted, at one and the same time, in Antiquity, the Renaissance and the Enlightenment. Amos Oz, in his autobiographical masterpiece A Tale of Love and Darkness, maintains that, in the era of nationalism between the two 20th-century world wars, the heirs of that European ideal were precisely those who by the millions were deprived of national status, the Jews.

“The only Europeans in the whole of Europe in the 1920s and 1930s were the Jews”, Oz writes. On his father’s side, Brandes is a son and grandson of those ‘self-aware Europeans’. And today he is the most European artist of Northern Europe. n Peter Brandes’ complex work for the exhibit “Fons Vitae” there are several levels of dialogue. First that with Leon Battista Alberti and his Holy Sepulchre structure. Brandes replicates the Sepulchre’s proportions, not however realizing a scale copy but making the measurements of his own composition perfectly faithful to the theory of concinnitas in Alberti’s De re aedificatoria (9, 5–6).

The central stained-glass element, on the floor, and the vertical one are realized in relationships of 2/1 e 3/2; the ten lateral scenes in relationships of 1/1 e 3/2; and the entire floor composition in relationships of 3/2 e 6/5. Except for the 6/5 relationship (corresponding to the musical relationship of terza minore), we have a spatial translation of harmonic musical relationships of unison, octave and fifth. Greater fidelity to the Pythagorean-Platonic-Albertian tradition is hard to imagine. This continuity becomes radical discontinuity, however, in the anti-classical expression of the design of the lateral stained-glass scenes. From left to right, counterclockwise, Brandes depicts: the Transfiguration on Mount Tabor, the Supper at Emmaus, the Birth of Christ, Easter Morning, the Baptism of Christ, Christ on the Cross (with the sponge steeped in vinegar), the Deposition, Mary with Christ, the Resurrection of Lazarus, and, once again, the Transfiguration. Without being able to comment each image, the motif that unites them is always the passage from life to death and from death to rebirth.

On his vertical glass, Brandes draws the figure that he has used since 1980 as an ideogram or signature for his pictorial writing. This form, in which Brandes conceals, among other things, the profile of the 6th-century B.C. lions from Delos and that of Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire, has been used by the artist across the decades as a generative font of ever-new forms and visual motifs [si propone: “Brandes used across the decades this form, in which he conceals, among other things, the profile of the 6th-century B.C. lions from Delos and that of Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire, as a generative font of ever-new visual motifs”].

At the center of the composition is a yellow glass that seems to recall the alabaster windows of the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia at Ravenna: the Resurrection. It is the light of resurrection that connects all the elements of the composition. The resurrection is that figure without form that gives meaning to the forms of the ten scenes that surround it. Just as, in the empty tomb, the presence of the risen Christ is felt precisely in his physical absence. Drawing on the vertical glass what can almost be understood as a self-portrait, Brandes has portrayed each of us and the capacity we all have to generate forms and actions. The vertical glass is the point of a ladder rising from the yellow glass. The light of the resurrection thus becomes the means by which we enter into dialogue with the Gospel stories of the side scenes, and, in the last analysis, the light-filled opening through which we enter into relationship with ourselves.

Maja Lisa Engelhardt

Bio

Since her debut in 1985, Maja Lisa Engelhardt (1956) has concentrated her artistic career, which includes painting, sculpture, graphics, ceramics, stained glass and textures, on issues that aim to describe the invisible God and His incarnation on earth in Christ. This aim, to the limits of the impossible, is expressed with landscapes rather than with human portraits. The presence of God is a column of cloud or a burning bush and the presence of His Son in the landscape is shown more with His absence than with His visible presence. Maja Lisa Engelhardt’s artistic research has manifested itself in the decoration of over 30 churches, in exhibitions in Scandinavia and in the United States, in a long series of publications on her works and of illustrations of texts such as the Bible and literary works. Her works are part of permanent collections of museums and public buildings.

Questa domanda continua a essere la stella che guida il cammino artistico di Maja Lisa Engelhardt. Basti guardare i suoi paesaggi degli anni Novanta e degli anni Zero, da Campo a Via attraverso il paesaggio, da Lago a Tronco nel paesaggio, tutti temi dipinti più e più volte. Questa domanda assume poi un respiro cosmico nei cicli di opere sui sette giorni della creazione, da Il primo giorno (2006) a Il settimo giorno (2017). Qui il compito impossibile diventa dipingere la natura cosmica nella semplicità dell’Inizio: la luce, le tenebre, lo spazio, il tempo, la vita vegetale, animale e umana. Maja Lisa Engelhardt dà senso alla proposta di Carl Gustav Carus (1789-1869): trasformare la pittura di paesaggio in Erdlebenbildkunst, alla lettera “arte delle immagini della vita della terra”, dunque immagini della forza vitale della natura, sia di quella selvaggia e potente, sia di quella “più silenziosa e semplice”, una vita di cui l’essere umano e il suo dare forma alla natura sono parte.

C’è tuttavia un elemento decisivo che distacca Maja Lisa Engelhardt dalla pittura romantica della natura. Gli Erdlebenbilder di Maja Lisa Engelhardt fanno sempre più tutt’uno con i suoi dipinti su motivi vetero- e neotestamentari su cui si sono concentrati gli ultimi vent’anni della sua opera. Non si può tracciare una chiara linea di demarcazione tra le sue opere che hanno come motivo la vita della natura e quelle su motivi biblici. Le opere sui due motivi si intrecciano, traggono forza le une dalle altre, fino a trapassare le une nelle altre e diventare indistinguibili.

Ne sono testimonianza le due sculture in bronzo esposte nella mostra Fons vitae: un monumento funebre, intitolato Resurrezione (2013-20) e La porta (2016), realizzata in occasione del 500° anno dell’affissione delle Tesi di Lutero sulla porta della Schlosskirche di WittenbergIn Resurrezione la sagoma luminosa del Cristo risorto esce dalla roccia oscura che lo circonda come una veste. Cristo porta con sé l’intera natura: la sua resurrezione diventa resurrezione cosmica, ottavo giorno della creazione. Ne La porta un piccolo squarcio di luce liquida nella superficie oscura diventa una cascata di luce e acqua dall’altra parte della porta. La fonte della vita, che stava per disseccarsi, può traboccare di nuovo. La fonte della vita del cristianesimo diventa di nuovo visibile. Entrambe le sculture mostrano le reciprocità tra forza della natura e forza della fede; sono al tempo stesso Erdlebenbilder e immagini della vita della fede. Maja Lisa Engelhardt così resta fedele all’intento di Lundbye: esprimere la natura e la fede, esprimere la nuova immediatezza.

To achieve immediacy in the representation of nature: this might be Maja Lisa Engelhardt’s motto as artist. The roots of her painting style should be sought in Northern romanticism, and especially in the Danish landscape artist Johan Thomas Lundbye (1818-48), who formulated his pictorial problem as a return to lost simplicity, immediacy, un-self-consciousness—even though he knew that return was impossible. For Lundbye the solution to this paradox was the search for a second and new immediacy in painting landscapes, which for him coincided with faith and love.

Could one ever express a new immediacy in painting landscapes, animals and human beings? This question remained unanswered in the brief life of Lundbye, who died in war at 29 years of age.

The same question continues to be the star guiding Maja Lisa Engelhardt’s artistic journey. It is sufficient to lok at her landscapes of the 1990s and first decade of the 21st century, from Field to Road through the Landscape, from Lake to Trunk in a Landscape, all themes to which she has returned time and again. The question assumes cosmic dimensions in her series of works on the seven days of creation, from The First Day (2006) to The Seventh Day (2017), where the impossible task becomes painting cosmic nature in the simplicity of its Beginning: light, shadow, space, time, vegetable, animal and human life. Maja Lisa Engelhardt makes sense of the proposal of Carl Gustav Carus (1789-1869) to transform landscape painting into Erdlebenbildkunst, literally “the art of images of the earth’s life”—images of the vital force of nature, both wild and powerful and “more silent and simple”: a life of which the human being and his giving of form to nature are part.

There is however one decisive element that separates Maja Lisa Engelhardt from Romantic nature painting. Maja Lisa’s Erdlebenbilder are always one with the paintings of Old and New Testament themes which have dominated the last twenty years of her work. It is not possible to draw a clear dividing line between her works treating the life of nature and those on biblical subjects. Her works on the two themes intertwine, drawing force from each other, to the point that each theme passes over into the other and they become indistinguishable.

Her two bronze sculptures in the exhibition Fons Vitae bear witness to this fact: a funerary monument, entitled Resurrection (2013-20) and The Door (2016), realized for the 500° anniversary of Luther’s nailing his Theses to the door of the Castle Church of Wittenberg. In Resurrection the luminous outline of the Risen Christ emerges from the dark rock that surrounds him like a garment. Christ brings all nature with him: his resurrection becomes the resurrection of the cosmos, the Eighth Day of creation. In The Door a small gash of liquid light in the dark surface becomes a cascade of light and water on the door’s other side. The font of life, which was about to dry up, can again overflow. The font of life of Christianity becomes visible again. Both sculptures show the reciprocity between the force of nature and the force of faith; they are at the same time Erdlebenbilder and images of the life of faith. Maja Lisa Engelhardt thus remains faithful to Lundbye’s goal to express nature and faith with the new immediacy.

Filippo Rossi

Bio

Filippo Rossi (1970), who has been exhibiting since 1994, explores the themes of Christian sacred art for over 10 years. After training in the life drawing school at the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence, he graduated in art history from the University of Florence. Since 1997 he has been Visiting Professor at the Stanford University Centre for Overseas Studies in Florence. He also collaborates with the art historian Timothy Verdon at the Curia of the Archdiocese of Florence, where he is currently Coordinator of the Diocesan Office of Sacred Art. His works are conserved in museums and collections both in Italy and abroad.

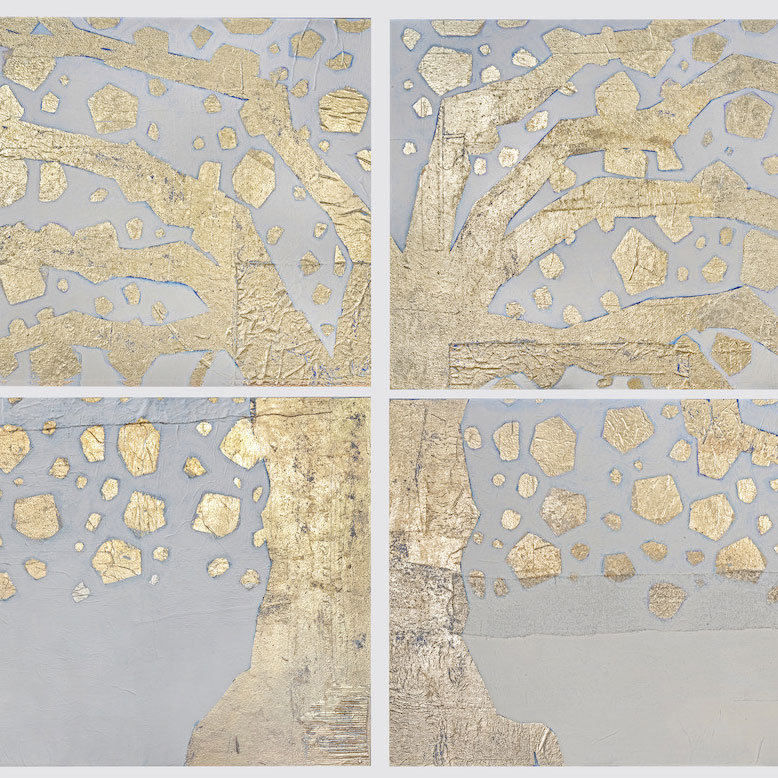

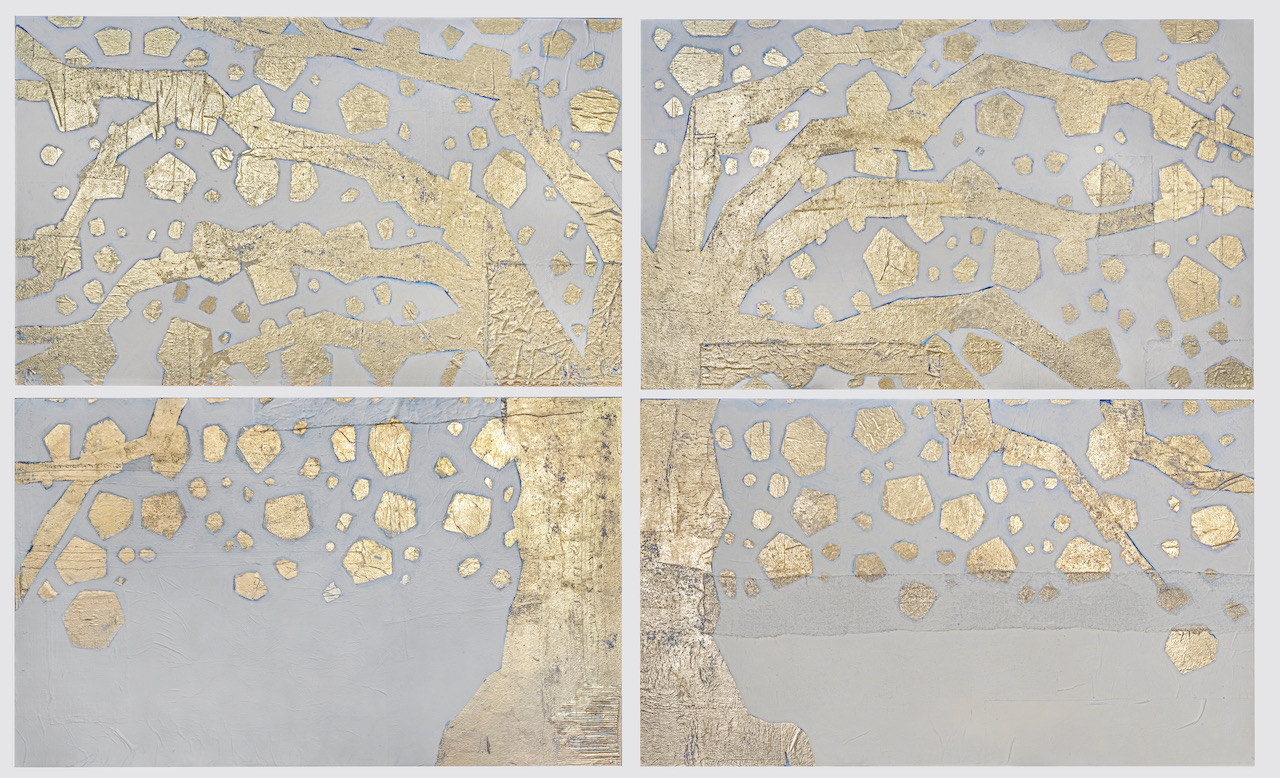

Come suggeriscono le sue opere in Fons Vitae, fondamentale per Rossi è questa tensione tra ‘visibile’ e ’invisibile’. La sua tesi di laurea, all’Università di Firenze, dove ha studiato la storia dell’arte, era sulle paci rinascimentali: le piccole tavole dipinte o in metallo sbalzato o inciso poste sugli altari durante la celebrazione della Messa, che poi venivano portate ai fedeli perché questi le baciassero al momento della comunione del celebrante. All’epoca i laici ricevano il sacramento poche volte all’anno, e le paci, con immagini allusive al tema eucaristico – la crocifissione, la imago pietatis, il compianto – invitavano a unirsi in modo immaginativo al sacerdote che consumava materialmente il pane e il vino transustanziati. L’immagine visibile sostituiva la realtà invisibile, cioè, senza però confondersi con essa, perché nel cattolicesimo latino l’immagine rimane solo immagine, mentre il pane e vino consacrati della Messa sono ‘reale presenza’ del corpo e sangue di Cristo. Le paci presupponevano, nei fedeli che le contemplavano e baciavano, la capacità di capire che la ‘realtà’ era altrove, non nella raffigurazione, ma nella ‘presenza’, non nella visibilità di eventi presentati agli occhi, ma nell’invisibile Persona adorata nel cuore.

Un passo ulteriore compiuto da Rossi fu infatti quella che nella tradizione cattolica è denominata ‘adorazione eucaristica’. Quando, nella parrocchia che Filippo frequentava per molti anni, s’instaurò la pratica di esporre agli occhi dei fedeli in modo continuativo il pane consacrato, invitando all’adorazione, egli fu tra quelli che garantivano la presenza notturna, recandosi in chiesa anche nelle ore piccole per restare inginocchiato davanti al disco di pane bianco esposto in un contenitore d’oro, l’ostensorio, in mezzo a candele la cui fiamma viva segnala la presenza del Salvatore. Queste componenti atmosferiche – i punti luce nel buio, l’aura del silenzio e di solitudine condivisa – segneranno l’arte di Rossi.

Ricordiamo poi che l’esperienza mistica di cui stiamo parlando ha precise coordinate sia filosofiche che estetiche: da una parte lo scarto sperimentale tra ‘segno’ e ‘realtà’, e dall’altra il bianco dell’ostia e delle tovaglie d’altare, l’oro dell’ostensorio e dei candelabri, il mobile brillare dei ceri. Giovanni Paolo II, in un testo che Rossi lesse appena pubblicato, la stupenda Lettera agli artisti del 1999, evocava tale estetica liturgica con una frase del teologo Pavel Flofrenskij, che, parlando delle icone russe, diceva: “L’oro, barbaro, pesante, futile nella luce del giorno, con la luce tremolante di una lampada o di una candela si ravviva, poiché sfavilla di miriadi di scintille ora qua, ora là, facendo presentire altre luci non terrestri che riempiono lo spazio celeste”.

La scelta del Rossi – visibile nella mostra Fons Vitae – , di arricchire di foglio d’oro le sue opere, nasce in questo clima.

To speak of Filippo Rossi’s art, the only possible point of departure is the artist’s Christian belief. Rossi lives his own creativity, and conceives his images, within the dynamic that the New Testament describes as ‘faith’. “Only faith can guarantee the blessings that we hope for, or prove the existence of the realities that at present remain unseen” says the author of the Letter to the Hebrews (11,1), adding almost immediately that “it is by faith that we understand that the world was created by one word from God, so that no apparent cause can account for the things we can see (Heb 11,3). The Latin Vulgate renders the idea that only faith guarantees our hopes by speaking of it with a less conceptual, more physical term, substantia, and Dante, who knew the Latin text, said: “Fede è sustanza di cose sperate e argomento de le non parventi, e questa pare a me sua quiditate” – “Faith is the substance of the things we hope for and the argument in favor of those we do not see, and this seems to me its quiddity” (Paradise XXIV, 64-65). Filippo Rossi, a believer and a Florentine, gives substance to what he hopes and argues in favor of what he cannot see, convinced that just as the material world had its origin in God’s immaterial word, so visible images can be born from the action of the invisible Spirit, since in Jesus Christ the Word became flesh.

As the works in Fons Vitae suggest, for Rossi this tension between ‘visible’ and ‘invisible’ is fundamental. His dissertation at the University of Florence, where he studied art history, was on Renaissance pax images: the small painted or metalwork objects positioned on altars during the celebration of Mass, which then were brought to the faithful attending so they might kiss them while the priest received communion. At that time layfolk rarely received the sacrament, and pax images, which allude to the Eucharistic theme – images of the crucifixion, imago pietatis, the Lamentation – invited believers to use their imagination to join the priest who was materially consuming the transubstantiated bread and wine. The visible image took the place of the invisible reality, that is, without being confused with it, since in Western Catholic practice the image remains only image, while the bread and wine consecrated at Mass are the ‘real presence’ of Christ’s body and blood. Pax images took for granted, in the faithful who contemplated and kissed them, a capacity to understand that the ‘reality’ was elsewhere, not in the representation but in the ‘presence’, not in the visibility of events brought before one’s eyes but in the invisible Person adored in one’s heart.

A further step Rossi took was in fact that which Catholic tradition calls ‘Eucharistic adoration’. When the parish that Filippo frequented for many years decided to expose the consecrated bread to the faithful in a continuous way, inviting all to adoration, our artist was among those who committed to be present at night, going to church in the wee hours to remain on his knees before a disk of white bread in a gold container, the monstrance, amid candles whose living flame signaled the Savior’s presence. These atmospheric elements – the points of light in the dark, the aura of silence and shared solitude – would mark Rossi’s art.

We should remember that the mystical experience described here has precise philosophical and esthetic coordinates: on the one hand, the experiential divergence between ‘sign’ and ‘reality’, and on the other the whiteness of the host and altar linens, the gold of the monstrance and candlesticks, the flickering glow of the candles. John Paul II, in a text that Rossi read as soon as it was published, the stupendous Letter to Artists of 1999, evoked this liturgical aesthetic with a phrase of the theologian Pavel Flofrenskij, who, speaking of Russian icons, said: “By the flat light of day, gold is crude, heavy, useless, but by the tremulous light of a lamp or candle it springs to life and glitters in sparks beyond counting—now here, now there, evoking the sense of other lights, not of this earth, which fill the space of heaven” (no. 8).

Rossi’s choice – visible in the works in Fons Vitae – to enrich his art with gold leaf, is born in this climate.

Susan Kanaga

Bio

Susan Kanaga is a member of the Community of Jesus since 1983. She has a Bachelor of Fine Arts Degree in painting from the Maine College of Art, a Bachelor of Arts Degree from Denver University, and an associate’s degree in paralegal studies from Rockhurst University. She has also studied the art of mosaic in Ravenna with Alessandra Caprara, of Mosaici Antichi e Moderni and helped realize the mosaic pavement of the Church of the Transfiguration, at Orleans, MA. In 2004 Susan was commissioned to design a cycle of stone sculptures on the theme of the Creation for the atrium of the Church of the Transfiguration. Susan is currently living in Lucca, Italy, and taking master lessons in non-figurative sacred art under Filippo Rossi’s direction.

Analogamente biblico e teologico è il giardino fiorito della mostra Fons Vitae, dove con 140 piccoli quadri la Kanaga evoca un tema amato dai monaci del Medioevo: quello del ‘paradiso’ del Libro della Genesi 1, 11-13 e dell’Apocalisse 22,2. I fiori luminosi di Susan Kanaga, e le rocce che sprigionano luce, ricordano che nell’universo redento “non vi sarà più notte” e, al posto del sole, sarà Dio stesso a illuminare i salvati (Apocalisse 22, 5).

Nella sua arte recente Susan Kanaga affronta i temi intangibili di fede, speranza e amore. Afferma che questi misteri eterni sfidano le sue credenze cristiane ma la spingono a dipingere. Sono concetti che vanno oltre la ragione, e qualche volta eludono la nostra comprensione. Tuttavia, l’artista prova una sensazione di connessione, una comunione attraverso l’atto del dipingere, che trasmette un’essenza senza parole.

Due domande guidano il lavoro della Kanaga: Qual è la presenza di assenza? E, come si fa a creare una forma senza forma? Ha scoperto che l’arte astratta consente una vasta gamma di possibilità per trasmettere idee centrali per il suo lavoro sul “Verbo fattosi carne”, Gesù Cristo.

Tra il 2013 al 2017 ha studiato con Filippo Rossi e con lui ha realizzato più mostre. Eppure, mentre apprezza la pura astrazione, cerca nel suo lavoro un contenuto solido con elementi riconoscibili quali simboli, espressi attraverso il colore e la forma. Per questo motivo, spesso introduce nelle sue opere le scarpe. Come simbolo, dice, la scarpa è utilitaristica e universale, un elemento tra passato e presente. Nell’immaginazione vede angeli che indossano scarpe, e questo per lei rende l’invisibile più tangibile e reale.

Nel suo lavoro utilizza il linguaggio del colore, un potente veicolo di espressione, quando abbinato a una attenzione materica alla superficie dell’opera. In questo modo, concetti ultraterreni diventano tattili e presenti nel qui ed ora. Il sacro trova una casa nella quotidianità, e per questa artista la vera spiritualità è la realtà del quotidiano.

Susan Kanaga vive e lavora attualmente a Lucca.

A member of the Community of Jesus, an ecumenical monastic family in the Benedictine tradition based in Orleans, Massachusetts (USA), Susan Kanaga has studied in the united States, the United Kingdom and Italy, contributing important works to the Community church inaugurated in the early 21st century, called Church of the Transfiguration. Hers is the design of the carved capitals of the open atrium preceding the church, which tell the Genesis story of creation. Together with the atrium’s monumental bronze doors depicting Adam and Eve, the capitals recount the beginning of history for all who prepare to enter the church, in whose apse an enormous mosaic of Christ in glory suggests history’s end, the ‘Parusia’ or final appearing of the world’s Savior, Alpha and Omega of all things.

Similarly biblical and theological in character is Kanaga’s flowering garden in Fons Vitae, where with 140 small paintings she evokes a theme dear to medieval monks, that of the ‘paradise’ described in Genesis 1, 11-13 and in Revelation 22,2. Her luminous flowers and rocks emanating light remind us that in the redeemed universe “night will be no more” and, instead of sunlight, God himself will illuminate the saved (Revelation 22,5).

In her recent art Susan Kanaga treats intangible themes of faith, hope and love. She says that these eternal mysteries challenge her Christian beliefs put push her to paint. They are, she says, concepts beyond rationality that somehow elude our understanding. Nonetheless, Kanaga experiences a feeling of connectedness, of communion, in the act of painting, which transmits essence without the use of words.

Two questions have guided her work: What is the presence of absence? And how can one create a formless form? She has discovered that abstract art permits a vast range of possibilities for transmitting ideas that are central in her work, such as “the Word became flesh”.

Between 2013 and 2017 she studied with Filippo Rossi and realized several exhibitions with him. Yet, although she appreciates pure abstraction, Susan Kanaga’s work seeks solid contents and recognizable elements used as symbols and expressed in form and color. It is for this reason that she often uses shoes, for, she says, as symbol shoes are utilitarian and universal, elements that bridge past and present. In her imagination she sees angels who wear shoes, and this makes the invisible tangible for her, and real.

In her work Susan Kanaga uses the language of color, a powerful vehicle of expression when combined with material care of surface. In this way, otherworldly concepts become tactile and present in the here and now. The Sacred finds a home in the everyday, and – for this artist – true spirituality is quotidian reality.

Susan Kanaga lives and works in Lucca, Italy.

Rinascenza come Resurrezione

Il Santo Sepolcro di Leon Batista Alberti nella Firenze del Quattrocento

Renaissance as Resurrection

Alberti’s Holy Sepulchre in 15th-century Florence